Is the Developing Great Teaching systematic review a cornerstone in an edifice of error, a key component of a mistaken ‘consensus’ around the evidence about effective teacher professional development and learning?

This is what Harry Fletcher-Wood Sam Sims assert in their piece in the TES on 21st September – [on-line here] and their more detailed article.

We have written (in the same TES edition with a fuller treatment in TES online) about their misunderstandings of the nature and value of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. We have discussed the broader concerns (and confusions) around the uses and limitations of these high level evidence syntheses in a series of blogs curated on the CEM website.

Here, we want to move away from the theoretical and methodological and focus in detail on the content of the Sims/Fletcher-Wood critique. We should say again that we entirely recognise and respect their right to offer this critique. We, in turn, think we have an obligation to address them and, where justified, refute them. We believe that, by doing this, we are contributing to the advancement of knowledge. That said, we should warn the reader that this gets pretty specific and maybe a bit nerdy for anyone not deeply interested in CPDL .

The missing bits

The authors assert “…, the consensus view is that PD which is sustained, collaborative, has buy-in from teachers and school leaders, is subject-specific, draws on external expertise and is practice-based is more effective than PD which is not”.

We do not recognise our meta-analysis as belonging to this assertion about consensus or that there is, in fact, a consensus at all. In any case, their version of this ‘consensus’ omits some core findings from Developing Great Teaching and mis-states others

Importance of different characteristics

Fletcher-Wood and Sims assert that “Generally, no claims are made about the relative importance of different characteristics,, which means that a programme containing more of the six characteristics cannot necessarily be assumed to be better than one containing fewer”. We are puzzled by this. We found that “no individual or combination of characteristics is common across the most reliable reviews, studies and claims”. By contrast, we did say that what is common and essential is “careful alignment of CPD activities and experiences with participants’ goals for their pupils”.

Having noted their omission of the one claim we do make about a common feature across all reviews, what then do we say about the “relative importance of different characteristics”?

Sustained

Although we find that CPDL which has big effects is usually sustained, we also note that CPDL with very specific and narrow goals - for example, developing a targeted approach to a specific aspect of spelling - can have a big impact on that narrow aspect of learning in much shorter timescales. What is key is the distance participants have to travel.

Collaborative

The DGT findings about collaboration are that “its effectiveness is contested. All the reviews with strong and positive evidence about effectiveness included an of peer support as a common feature. The strongest review found that collaboration was necessary, but not sufficient, being linked to both positive and negative outcomes”. For example, collaboration in the form of professional learning communities was not effective unless it was highly structured and focussed on specific goals for pupils. We found some evidence to suggest that access to some form of collegial support in addressing and solving important work place problems in applying learning from specialists is key and this frequently included combinations of peer and or specialist coaching. So collaboration in DGT is highly structured (around aspirations for pupils, as is everything else), intimately connected with specialist expertise and often part of it.

Buy-in

Far from saying that CPD has to have buy in from teachers and leaders we point out that effective CPD works just as well for conscripts as for volunteers:

- For teachers – we found that CPDL worked for conscripts provided the activities are aligned around concrete aspirations for progress for participants’ pupils. The alignment with aspirations for pupils is key to converting CPD support offered to teachers, to CPDL; learning by teachers as they test approaches offered by specialists (and research) to refine their own practice.

- For school leaders – We agree that the review did conclude that “effective leaders did not leave the learning to their teachers – they became involved themselves”. In other words, we found that leaders were promoting or giving status to professional learning by contributing to it and modelling it. But this was in the context of findings about whole school CPD leadership which identified four core roles for school leaders in effective CPDL, which were adapted according to the school context and the nature of changes being implemented:

- Developing vision – includes helping teachers believe alternative outcomes are possible, creating coherence so teachers understand the relevance of CPD to wider priorities

- Managing and organising – includes establishing priorities, resolving competing demands, sourcing appropriate expertise and ensuring appropriate opportunities to learn are in place

- Leading professional learning – includes promoting a challenging learning culture, knowing what content and activities are likely to be of benefit, and promoting “evidence-informed, self-regulated learning”

- Developing the leadership of others – includes encouraging teachers to lead a particular aspect of pedagogy or of the curriculum.

Subject specific

We agree that we found that CPDL that focusses on generic pedagogy and does not give teachers opportunities to contextualise support for pedagogy for their subjects (and sub groups of pupils) is not effective.

Omissions

What is missing are findings about:

· Differentiation and formative assessment for teachers. All the reviews also noted the importance of CPDL which provides opportunities for taking account of differences between individual teachers and their starting points. We found also that CPDL content needed to secure clarity around what learner progression, starting points and next steps would look like if what teachers were learning was successful. In other words we found that formative assessment for teachers matters too.

· Reviewing beliefs and assumptions - All the reviews also noted the importance of CPDL which provides opportunities for them to surface their beliefs. The key here was to review and refine existing beliefs and assumptions about, for example, their pupils’ abilities and or curriculum content in the light of evidence from their pupils and from wider research - which was very often, but not always, achieved through peer support.( We have argued elsewhere that peer support is an efficient and effective context for reviewing and refining beliefs and assumptions because and the acceleration in trust which arises from share risk taking between peers).

· Persistence to enable the grasp the underpinning rationale - The review found that CPDL “programme design needs to create a “rhythm” of follow-up, consolidation and support activities to reinforce key messages enough to have an impact. The specific frequency of these activities varied, but the key aim remained constant – teachers must develop a grasp of the rationale underpinning a strategy being explored through CPDL, and use that understanding to refine practices and support implementation”.

· Coaching and external expertise - Sims and Fletcher-wood argue that “In general (in the consensus) outside expertise is used to mean input from people that do not work in the same school as the teachers receiving the training. The justification for this is generally that this is needed to provide challenge or fresh input, as opposed to recycling existing expertise from inside the school, with which teachers may already be familiar”. We agree that we found that expert input is a common factor in successful outcomes. But there are important details omitted in their argument. For example, we found that “external input was sometimes in tandem with internal specialists”. Similarly, “in the most successful CPDL, external input includes both providing multiple and diverse perspectives, and challenging orthodoxies”. External specialists did many things, some of which are consistent with what Sims and Fletcher Wood describe as instructional coaching, an alignment which they do not mention: “Providers of the most successful CPDL also act as coaches and/or mentors with participants, and there is some evidence to suggest that they are experts in more than one area and their expertise includes both specialist content knowledge and in-depth knowledge of professional development processes and evaluation and monitoring”. The review also identified a series of types of activity which specialist support (or instructional coaching) “should, according to the evidence analysed, lead to successful outcomes:

o Making the public knowledge base, theory and evidence on pedagogy, subject knowledge, and strategies accessible to participants

o Introducing new knowledge and skills to participants

o Helping teachers (particularly those from schools where achievement is depressed over time) believe better outcomes are possible (according to the strongest study)

o Making links between professional learning and pupil learning explicit through discussion of pupil progression and analysis of assessment data

o Taking account of different teachers’ starting points and (from the strongest review) the emotional content of the learning

o Specialists should also support teachers through modelling, providing observation and feedback, and coaching”

And what of the CPD Standards?

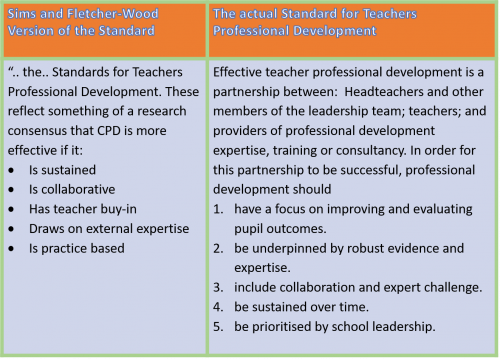

Lastly, we want to look at Sam Sims and Harry Fletcher-Wood’s argument that “The apparent consensus developed through these reviews has directly influenced and become embedded in official guidance in the UK”. It is true that developing Great Teaching influenced the standards -which we are generally quite pleased about – but so did many other people and other evidence. But those Standards are rather different from the version of them set out in the Sims/Fletcher-Wood paper as the table below shows clearly

..and Finally

Progress in educational methods and educational research is usually painstaking, detailed, slow and, frankly, boring. To grab a headline and, we sometimes think, the attention of teachers and policy makers, we feel the need to simplify and, if we can, create an adversary as Michael Gove did with his ‘Blob’.

Harry Fletcher-Wood and Sam Sims have the right to attack what they apparently think is an establishment consensus. We don’t accept that Developing Great Teaching should feature as a straw man in their battle